Algiers: a city where France is the promised land – and still the enemy

Andrew Hussey believes the only way to makes sense of the problems Algeria faces today is to look back into its colonial history. He takes a journey through 21st-century Algiers – into a dark past

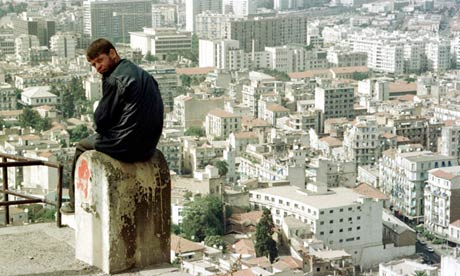

A man sits overlooking Algiers from the old city. Photograph: Ouahab/AP

During the past few weeks, the terrible violence in Mali and Algeria has shocked the world. The events have also reminded us how much of Africa

is still French-speaking and how deep French influence still runs in

those territories. More than this, the conflicts have reminded everybody

else that the French still regard this part of their world as their

backyard

The long French involvement in African affairs, from Rwanda to north Africa, has also been marked by bloody massacres and torture. This is especially true of Algeria, the largest country in Africa, first conquered by the French nearly 200 years ago. Algeria gained its independence in 1962, after a hard-fought war against France, notable for the use of terrorist tactics and torture on both sides.

Poverty and terrorism are still ever-present in Algerian life. At the same time, as the focus of the Arab Spring shifts to north Africa, it is also shifting nearer to France, which has the largest Muslim population in Europe.

It's hardly surprising, then, that the French are becoming increasingly sensitive to changing moods in the Muslim world and especially Algeria. Indeed, this is not the first time that events in north Africa have threatened to spill over into France. In the 90s, when Algeria became a slaughterhouse and tens of thousands were killed in the dirty war between the government and Islamist insurgents, Paris was the chief target of Algerian extremists. In 1995, Abdelbaki Sahraoui, a moderate imam, was gunned down in northern Paris by the terrorist Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA). His death was followed by a swift succession of bombings on civilian targets in Paris that left eight dead and more than 100 wounded.

More recently, France was convulsed by a series of murders over nine days last March including three French soldiers of north African descent killed in two separate shootings, and a rabbi, his two young sons and a third child in an attack on a Jewish school in Toulouse. The rage only intensified when it became known that the killer was Mohamed Merah, a young French citizen of Algerian origin. Before Merah was shot dead in an armed police siege of the block of flats where he lived, he declared that he wanted to "bring France to its knees".

Many ordinary Algerians wanted to pass the affair off as an internal French matter and did not want to be contaminated by association. There was much loud anger in the Algerian press about the way in which the murders were linked to Merah's Algerian origins: this was pure racism for many. But none of this stopped Merah becoming a hero, praised as "lion", in the radical mosques of Algiers. Fifty years on from their last real war, it seems that France and Algeria are still quite capable of tearing each other's throats out.

I first saw for myself the rawness of these emotions when I went to study in France in 1982. I ended up living on the outskirts of Lyon, which is where the first so-called urban riots kicked off – the precursors of the riots of the 2000s. Throughout that summer – the "hot summer" – cars were regularly set alight by immigrant youths who called this kind of entertainment "rodeos" and who declared war on the police. The centre of the violence was the cité (housing estate) in Vénissieux called Les Minguettes.

At the time, I knew little about French colonial history and assumed that these were race riots not much different to those we had known in the UK in 1981. But I was aware that most of the kids who were fighting the police were of Algerian origin and that this must have some kind of significance.

Thirty years on, the unresolved business between France and Algeria has grown ever more complex. That is why last year I launched a Centre for the Study of France and North Africa (CSFNA) at the University of London Institute in Paris (ULIP) where I am dean. The overall aim of the centre is to function as a thinktank, bringing together not just academics but all those who have a stake in understanding the complexities of Franco-Algerian history; this necessarily involves journalists, lawyers and government as well as historians.

At the same time, I am writing a book called The French Intifada, which is a parallel attempt to make sense of French colonial history in north Africa. This book is a tour around some of the most important and dangerous frontlines of what many historians now call the fourth world war. This war is not a conflict between Islam and the west or the rich north and the globalised south, but a conflict between two very different experiences of the world – the colonisers and the colonised.

The French invaded Algeria in 1830. This was the first colonisation of an Arab country since the days of the Crusades and it came as a great shock to the Arab nation. This first battle for Algiers was a staged affair. Pleasure ships sailed from Marseille to watch the bombardment and the beach landings. The Arab corpses that lay strewn in the streets and along the coastline were no more than incidental colour to the Parisian spectator watching the slaughter through opera glasses from the deck of his cruise ship.

The trauma deepened as, within a few short decades, Algeria was not given the status of a colony but annexed into France. This meant that the country had no claim to any independent identity whatsoever, but was as subservient to Parisian government as Burgundy or Alsace-Lorraine. This had a deeply damaging effect on the Algerian psyche. The settlers who came to work in Algeria from the European mainland were known as pieds-noirs – black feet – because, unlike the Muslim population, they wore shoes. The pieds noirs cultivated a different identity from that of mainland Frenchmen.

Meanwhile, Muslim villages were destroyed and whole populations forced to move to accommodate European farms and industry. As the pieds-noirs grew in number and status, the native Algerians, who had no nationality under French law, did not officially exist. Albert Camus captures this non-identity beautifully in his great novel L'Etranger (The Outsider): when the hero Meursault shoots dead the anonymous Arab on an Algiers beach, we are only concerned with Meursault's fate. The dead Arab lies literally outside history.

Like most Europeans or Americans of my generation, I had first come across Algiers and Algeria in Camus's writings, not just in L'Etranger but also his memoirs and essays. And like most readers who approach Algeria through the prism of Camus, I was puzzled by this place, which, as he described it, was so French that it might have been in France but was also so foreign and out of reach.

Part of this difficulty arises from the fact that the Algeria Camus describes is only partly a Muslim country. Instead, Camus sees Algeria as an idealised pan-Mediterranean civilisation. In his autobiographical writings on Algiers and on the Roman ruins at Tipasa, he describes a pagan place where classical values were still alive and visible in the harsh but beautiful, sun-drenched landscape. This, indeed, is the key to Camus's philosophy of the absurd. In his Algeria, God does not exist and life is an endless series of moral choices that must be decided by individuals on their own, with no metaphysical comfort or advice, and with little or no possibility of knowing they ever made the absolutely correct choice.

It is easy to see here how Camus's philosophy appealed to the generation of French leftist intellectuals that fought in the second world war, a period when occupied France was shrouded in moral ambiguity as well as in the military grip of the Germans. It was less effective, however, in the postwar period, as Algerian nationalism began to assert itself against France, modelling itself on the values of the French Resistance.

Camus was sympathetic to the cause of Muslim rights. However, like most European algériens on the left, Camus spoke no Arabic and had little patience with religion, including Islam. Most importantly, throughout the 1950s, as violence between the French authorities and Algerian nationalists intensified, Camus found himself endlessly compromised. His intentions were always noble but by the time of his death in a car crash in 1960 he had acknowledged that he no longer recognised the country of his birth.

During the 90s, it became all but impossible to visit Algeria. Reading Camus as a way in to this Algeria was simply a waste of time. This was a country dominated by terror as the hardline government fought a shadowy civil war against Islamist insurgents who sought to turn Algeria into "Iran on the Mediterranean".

Algerian Muslims were regularly massacred by Islamist and other unknown forces. Foreigners were declared enemies by the Islamists, targeted for execution. The government could not be trusted either. The only non-Algerians who braved the country were hardened war reporters such as Robert Fisk, who described disguising his European face with a newspaper when travelling by car in Algiers and staying no more than four minutes in a street or a shop – the minimum time, he decided, for kidnappers to spot a European. In Algiers in the mid-90s, in this formerly most cosmopolitan of cities, an hour or so's flight from the French mainland, for Algerians and Europeans kidnap and murder were only ever a matter of minutes away.

Andrew Hussey, centre, at a north African cafe in the Parisian

district of Barbes. Photograph: Franck Ferville for the Observer

Andrew Hussey, centre, at a north African cafe in the Parisian

district of Barbes. Photograph: Franck Ferville for the Observer

The long French involvement in African affairs, from Rwanda to north Africa, has also been marked by bloody massacres and torture. This is especially true of Algeria, the largest country in Africa, first conquered by the French nearly 200 years ago. Algeria gained its independence in 1962, after a hard-fought war against France, notable for the use of terrorist tactics and torture on both sides.

Poverty and terrorism are still ever-present in Algerian life. At the same time, as the focus of the Arab Spring shifts to north Africa, it is also shifting nearer to France, which has the largest Muslim population in Europe.

It's hardly surprising, then, that the French are becoming increasingly sensitive to changing moods in the Muslim world and especially Algeria. Indeed, this is not the first time that events in north Africa have threatened to spill over into France. In the 90s, when Algeria became a slaughterhouse and tens of thousands were killed in the dirty war between the government and Islamist insurgents, Paris was the chief target of Algerian extremists. In 1995, Abdelbaki Sahraoui, a moderate imam, was gunned down in northern Paris by the terrorist Groupe Islamique Armé (GIA). His death was followed by a swift succession of bombings on civilian targets in Paris that left eight dead and more than 100 wounded.

More recently, France was convulsed by a series of murders over nine days last March including three French soldiers of north African descent killed in two separate shootings, and a rabbi, his two young sons and a third child in an attack on a Jewish school in Toulouse. The rage only intensified when it became known that the killer was Mohamed Merah, a young French citizen of Algerian origin. Before Merah was shot dead in an armed police siege of the block of flats where he lived, he declared that he wanted to "bring France to its knees".

Many ordinary Algerians wanted to pass the affair off as an internal French matter and did not want to be contaminated by association. There was much loud anger in the Algerian press about the way in which the murders were linked to Merah's Algerian origins: this was pure racism for many. But none of this stopped Merah becoming a hero, praised as "lion", in the radical mosques of Algiers. Fifty years on from their last real war, it seems that France and Algeria are still quite capable of tearing each other's throats out.

I first saw for myself the rawness of these emotions when I went to study in France in 1982. I ended up living on the outskirts of Lyon, which is where the first so-called urban riots kicked off – the precursors of the riots of the 2000s. Throughout that summer – the "hot summer" – cars were regularly set alight by immigrant youths who called this kind of entertainment "rodeos" and who declared war on the police. The centre of the violence was the cité (housing estate) in Vénissieux called Les Minguettes.

At the time, I knew little about French colonial history and assumed that these were race riots not much different to those we had known in the UK in 1981. But I was aware that most of the kids who were fighting the police were of Algerian origin and that this must have some kind of significance.

Thirty years on, the unresolved business between France and Algeria has grown ever more complex. That is why last year I launched a Centre for the Study of France and North Africa (CSFNA) at the University of London Institute in Paris (ULIP) where I am dean. The overall aim of the centre is to function as a thinktank, bringing together not just academics but all those who have a stake in understanding the complexities of Franco-Algerian history; this necessarily involves journalists, lawyers and government as well as historians.

At the same time, I am writing a book called The French Intifada, which is a parallel attempt to make sense of French colonial history in north Africa. This book is a tour around some of the most important and dangerous frontlines of what many historians now call the fourth world war. This war is not a conflict between Islam and the west or the rich north and the globalised south, but a conflict between two very different experiences of the world – the colonisers and the colonised.

The French invaded Algeria in 1830. This was the first colonisation of an Arab country since the days of the Crusades and it came as a great shock to the Arab nation. This first battle for Algiers was a staged affair. Pleasure ships sailed from Marseille to watch the bombardment and the beach landings. The Arab corpses that lay strewn in the streets and along the coastline were no more than incidental colour to the Parisian spectator watching the slaughter through opera glasses from the deck of his cruise ship.

The trauma deepened as, within a few short decades, Algeria was not given the status of a colony but annexed into France. This meant that the country had no claim to any independent identity whatsoever, but was as subservient to Parisian government as Burgundy or Alsace-Lorraine. This had a deeply damaging effect on the Algerian psyche. The settlers who came to work in Algeria from the European mainland were known as pieds-noirs – black feet – because, unlike the Muslim population, they wore shoes. The pieds noirs cultivated a different identity from that of mainland Frenchmen.

Meanwhile, Muslim villages were destroyed and whole populations forced to move to accommodate European farms and industry. As the pieds-noirs grew in number and status, the native Algerians, who had no nationality under French law, did not officially exist. Albert Camus captures this non-identity beautifully in his great novel L'Etranger (The Outsider): when the hero Meursault shoots dead the anonymous Arab on an Algiers beach, we are only concerned with Meursault's fate. The dead Arab lies literally outside history.

Like most Europeans or Americans of my generation, I had first come across Algiers and Algeria in Camus's writings, not just in L'Etranger but also his memoirs and essays. And like most readers who approach Algeria through the prism of Camus, I was puzzled by this place, which, as he described it, was so French that it might have been in France but was also so foreign and out of reach.

Part of this difficulty arises from the fact that the Algeria Camus describes is only partly a Muslim country. Instead, Camus sees Algeria as an idealised pan-Mediterranean civilisation. In his autobiographical writings on Algiers and on the Roman ruins at Tipasa, he describes a pagan place where classical values were still alive and visible in the harsh but beautiful, sun-drenched landscape. This, indeed, is the key to Camus's philosophy of the absurd. In his Algeria, God does not exist and life is an endless series of moral choices that must be decided by individuals on their own, with no metaphysical comfort or advice, and with little or no possibility of knowing they ever made the absolutely correct choice.

It is easy to see here how Camus's philosophy appealed to the generation of French leftist intellectuals that fought in the second world war, a period when occupied France was shrouded in moral ambiguity as well as in the military grip of the Germans. It was less effective, however, in the postwar period, as Algerian nationalism began to assert itself against France, modelling itself on the values of the French Resistance.

Camus was sympathetic to the cause of Muslim rights. However, like most European algériens on the left, Camus spoke no Arabic and had little patience with religion, including Islam. Most importantly, throughout the 1950s, as violence between the French authorities and Algerian nationalists intensified, Camus found himself endlessly compromised. His intentions were always noble but by the time of his death in a car crash in 1960 he had acknowledged that he no longer recognised the country of his birth.

During the 90s, it became all but impossible to visit Algeria. Reading Camus as a way in to this Algeria was simply a waste of time. This was a country dominated by terror as the hardline government fought a shadowy civil war against Islamist insurgents who sought to turn Algeria into "Iran on the Mediterranean".

Algerian Muslims were regularly massacred by Islamist and other unknown forces. Foreigners were declared enemies by the Islamists, targeted for execution. The government could not be trusted either. The only non-Algerians who braved the country were hardened war reporters such as Robert Fisk, who described disguising his European face with a newspaper when travelling by car in Algiers and staying no more than four minutes in a street or a shop – the minimum time, he decided, for kidnappers to spot a European. In Algiers in the mid-90s, in this formerly most cosmopolitan of cities, an hour or so's flight from the French mainland, for Algerians and Europeans kidnap and murder were only ever a matter of minutes away.

Andrew Hussey, centre, at a north African cafe in the Parisian

district of Barbes. Photograph: Franck Ferville for the Observer

Andrew Hussey, centre, at a north African cafe in the Parisian

district of Barbes. Photograph: Franck Ferville for the Observer

When I finally arrived in Algiers for the first time in 2009, the

city I found was not like this. The ceasefire and amnesty had been in

place for several years, although as recently as 2007 there had been a

wave of deadly bombings and assassinations. But although you no longer

had to hide your status as a European, the city was still tense. On the

drive from the airport, I passed no fewer than six police or military

checkpoints, all manned by heavily armed men. It was getting dark and

Algiers was emptying out for the night. During the long nightmare of the

1990s, nobody had dared to be out of doors after dark and the habit

remained.

As we drove against the rush-hour traffic towards my hotel in the centre, you could see that, along with Marseilles, Naples, Barcelona or Beirut, this was one of the great Mediterranean cities; in the dusk, I could still make out the pine forests of the surrounding hills and the magnificent dark-blue sweep of the bay. Unlike any of her sister cities, however, with maybe the exception of Gaza, Algiers went into lockdown at the first shadows of evening.

Over the next few days, I crawled all over the city, walking the boulevards, climbing steep streets and staring out at the sea from the heights. I spoke to everyone I could – teachers, shopkeepers, students, journalists, political activists. They were all remarkably frank, breathless and impatient to tell their stories to an outsider. Their suffering during the years of Islamist terror had been incalculable. An elegant university lecturer, a specialist in Marxism and feminism, told me how she went every day to classes at the university, driving past the headless corpses that were regularly pinned to the gates of the institute. A journalist recalled for me the vicious paranoia of everyday life in Algiers in the 90s, and how, as he walked down the street, bearded young men he did not know would hiss at him and make a throat-slitting gesture.

A young female student who had grown up in the "triangle of death" – the villages and suburbs controlled by terrorists just outside Algiers – recounted a childhood memory of washing other people's blood off her feet, having waded through the muddy streets of her village after a massacre. She delivered these facts in a cold, steady voice, obviously distancing herself from the nightmare for the sake of self-preservation.

Despite the horror stories, my exhilaration at first overcame fear. I had waited a long time to be here. In the past two decades, I had worked and travelled extensively in the sister countries of Morocco and Tunisia. All the time, I had been dreaming of visiting Algeria, of seeing Algiers, the capital of French north Africa.

Most of all, I wanted to see the Casbah – the old Ottoman city that runs from the hills of Algiers down to the sea. These days, the Casbah is a rotting slum. Its narrow and ancient streets stink of sewage. There are gaping holes left by unfinished renovation projects or by unloved houses that have shattered and collapsed from neglect. Many of the inhabitants mutter that the authorities would like to see the complete destruction of the Casbah, which they see as a haven for criminals and terrorists. There is talk, too, of property speculators who want to build hotels and shops on prime real estate. Still, this is the most iconic and historically significant space in north Africa.

Walking down through Algiers from the Casbah is an eerie experience. This is not because of the usual cliches about Arab or Ottoman cities – that they are "timeless", "medieval" and so on. These are meaningless European notions of chronology, urban order and modernity grafted on to the living reality of 21st-century Muslim life. Rather, the sense of the uncanny you meet during a first trip to Algiers is classically Freudian: it is the dream-like sense that, without knowing it, you have already been here before. This is partly because of the myriad films, books and paintings about and of the city that have made Algiers probably the most known unvisited capital in the world. It is also because walking through Algiers is like walking through the wreckage of a recently abandoned civilisation, whose citizens have only just departed in a hurry, leaving behind them their most personal possessions which you immediately recognise.

As you step down to the packed streets leading towards Place des Martyrs, the ruins of the French city begin to reveal themselves. As you go down past the Turkish-style mosque and the city widens towards the sea, the arcades, passages and the streets are constructed with the geometric precision to be found in any French town. The centre of gravity of the French city was here, between the rue d'Isly (now rue Larbi Ben M'hidi) and rue Michelet (now rue Didouche Mourad).

The streets may now be named after heroes of the war against France, but Algiers here is as purely French as Paris, Lyon or Bordeaux. This much is revealed in the details of the street – the street signs, the lamps, the carefully constructed squares, the blue-shuttered balconies, the old tram tracks and the cobbled paving stones. At the dead centre of the city is the Jardin de l'horloge, a compact garden terrace that looks out directly on to the harbour, and where the monument to the French dead who gave their lives for "Algérie Française" has been covered up. As in Venice or down by the port in Marseilles, passing ships seem so near that you feel you could walk on to them.

This is the cityscape that is lodged deep in French cultural memory, persisting in paintings, books and films as the emblem of the city. One of the enduring images of this part of Algiers appears in the final part of the 1937 movie Pépé le Moko. This tells the story of Pépé, a Parisian gangster played by Jean Gabin, who is on the run from the Parisian police and holed up in the Casbah. Pépé falls in love with Gaby, a young Parisian tourist, who evokes in him a longing for the Paris he has abandoned for his imprisonment in the Casbah.

In the final scene of the film, he risks capture by the police by leaving the Casbah and running down to the French city and the port, down to the ship where Gaby has embarked to return to France. He is arrested and led away. In a final gesture of love for Gaby (and the Paris she represents), he calls out to her, pushing against the steel gates that he cannot pass. As Pépé calls out to his lover, she cannot hear him. In frustration, Pépé takes out a pocket knife and stabs himself in the heart. The scene closes with a shot of Pépé's corpse stretched on the gates that have kept him in Algeria and cut him off from the ship that we then see bound for France. The drama of this moment is heightened all the more as it is clearly set against the backdrop of the French city and the Casbah – two worlds forever locked in mutual antagonism.

On my latest trip to Algiers, I climbed for the first time the hill to Notre Dame d'Afrique. This church is visible practically everywhere in Algiers, but on all my journeys to the city I had never got round to visiting it. During the 90s, there was a permanent police presence here and the priests were under 24-hour protection. When I got there, I found the atmosphere relatively relaxed. It was a sunny day and the esplanade around the church was thronged with families, picnicking, enjoying the views (which are some of the best in Algiers), kids playing football. The terrace overlooks the district of Bologhine, which contains the football stadium and the Christian and Jewish cemetery. The seafront houses look like a small town from Brittany or Normandy that has been grafted on to a Mediterranean vista.

Inside the church, a handful of elderly pieds-noirs were at prayer. I chatted to a few, who told me that this was still their home and that they prayed for peace, which they hoped for but never expected to see. Over the altar is the rubric "Pray for us and the Muslims".

Outside in the sunshine, I chatted to the families and children at play. I asked them if they had ever been inside the church. I asked one kid, about 10 years old, wearing a Chelsea shirt and kicking a ball, if he knew what the building was. "Eh bien oui," he said in perfectly accented Mediterranean French that could have come from Marseille, "ça c'est la mosquée des Roumis. Mais il n'y a plus de Roumis." Oh yeah – that's the mosque of the Romans. But there ain't no more Romans.

In Algiers in the 21st century, the French may have left but France is still the enemy. It also represents the promised land. By day, the streets of downtown Algiers are thronged with unemployed young men who dream of France but have no chance of getting the visas they need to get there. The visits by President Chirac in 2003, then Sarkozy in 2007, and, most recently, François Hollande at the end of last year have all been met by crowds chanting: "Give us our visas!"

The Algerians who have made it in France can find the atmosphere strange and unfriendly when they come back. Sinik, a rapper in Seine-Saint-Denis, came over and swore that he would never come again: he was met by heckling crowds and general indifference. For a whole generation, so-called democracy has made Algeria feel like a prison. They don't need to be taunted by those who have escaped.

No one really knows exactly when the last "war for liberation" ended. All everyone knows is that the rate of killing has slowed down but nobody feels free. The tension hangs in the air, waiting to be transformed again into an electric storm.

The French Intifada, by Andrew Hussey, will be published by Granta in the autumn

As we drove against the rush-hour traffic towards my hotel in the centre, you could see that, along with Marseilles, Naples, Barcelona or Beirut, this was one of the great Mediterranean cities; in the dusk, I could still make out the pine forests of the surrounding hills and the magnificent dark-blue sweep of the bay. Unlike any of her sister cities, however, with maybe the exception of Gaza, Algiers went into lockdown at the first shadows of evening.

Over the next few days, I crawled all over the city, walking the boulevards, climbing steep streets and staring out at the sea from the heights. I spoke to everyone I could – teachers, shopkeepers, students, journalists, political activists. They were all remarkably frank, breathless and impatient to tell their stories to an outsider. Their suffering during the years of Islamist terror had been incalculable. An elegant university lecturer, a specialist in Marxism and feminism, told me how she went every day to classes at the university, driving past the headless corpses that were regularly pinned to the gates of the institute. A journalist recalled for me the vicious paranoia of everyday life in Algiers in the 90s, and how, as he walked down the street, bearded young men he did not know would hiss at him and make a throat-slitting gesture.

A young female student who had grown up in the "triangle of death" – the villages and suburbs controlled by terrorists just outside Algiers – recounted a childhood memory of washing other people's blood off her feet, having waded through the muddy streets of her village after a massacre. She delivered these facts in a cold, steady voice, obviously distancing herself from the nightmare for the sake of self-preservation.

Despite the horror stories, my exhilaration at first overcame fear. I had waited a long time to be here. In the past two decades, I had worked and travelled extensively in the sister countries of Morocco and Tunisia. All the time, I had been dreaming of visiting Algeria, of seeing Algiers, the capital of French north Africa.

Most of all, I wanted to see the Casbah – the old Ottoman city that runs from the hills of Algiers down to the sea. These days, the Casbah is a rotting slum. Its narrow and ancient streets stink of sewage. There are gaping holes left by unfinished renovation projects or by unloved houses that have shattered and collapsed from neglect. Many of the inhabitants mutter that the authorities would like to see the complete destruction of the Casbah, which they see as a haven for criminals and terrorists. There is talk, too, of property speculators who want to build hotels and shops on prime real estate. Still, this is the most iconic and historically significant space in north Africa.

Walking down through Algiers from the Casbah is an eerie experience. This is not because of the usual cliches about Arab or Ottoman cities – that they are "timeless", "medieval" and so on. These are meaningless European notions of chronology, urban order and modernity grafted on to the living reality of 21st-century Muslim life. Rather, the sense of the uncanny you meet during a first trip to Algiers is classically Freudian: it is the dream-like sense that, without knowing it, you have already been here before. This is partly because of the myriad films, books and paintings about and of the city that have made Algiers probably the most known unvisited capital in the world. It is also because walking through Algiers is like walking through the wreckage of a recently abandoned civilisation, whose citizens have only just departed in a hurry, leaving behind them their most personal possessions which you immediately recognise.

As you step down to the packed streets leading towards Place des Martyrs, the ruins of the French city begin to reveal themselves. As you go down past the Turkish-style mosque and the city widens towards the sea, the arcades, passages and the streets are constructed with the geometric precision to be found in any French town. The centre of gravity of the French city was here, between the rue d'Isly (now rue Larbi Ben M'hidi) and rue Michelet (now rue Didouche Mourad).

The streets may now be named after heroes of the war against France, but Algiers here is as purely French as Paris, Lyon or Bordeaux. This much is revealed in the details of the street – the street signs, the lamps, the carefully constructed squares, the blue-shuttered balconies, the old tram tracks and the cobbled paving stones. At the dead centre of the city is the Jardin de l'horloge, a compact garden terrace that looks out directly on to the harbour, and where the monument to the French dead who gave their lives for "Algérie Française" has been covered up. As in Venice or down by the port in Marseilles, passing ships seem so near that you feel you could walk on to them.

This is the cityscape that is lodged deep in French cultural memory, persisting in paintings, books and films as the emblem of the city. One of the enduring images of this part of Algiers appears in the final part of the 1937 movie Pépé le Moko. This tells the story of Pépé, a Parisian gangster played by Jean Gabin, who is on the run from the Parisian police and holed up in the Casbah. Pépé falls in love with Gaby, a young Parisian tourist, who evokes in him a longing for the Paris he has abandoned for his imprisonment in the Casbah.

In the final scene of the film, he risks capture by the police by leaving the Casbah and running down to the French city and the port, down to the ship where Gaby has embarked to return to France. He is arrested and led away. In a final gesture of love for Gaby (and the Paris she represents), he calls out to her, pushing against the steel gates that he cannot pass. As Pépé calls out to his lover, she cannot hear him. In frustration, Pépé takes out a pocket knife and stabs himself in the heart. The scene closes with a shot of Pépé's corpse stretched on the gates that have kept him in Algeria and cut him off from the ship that we then see bound for France. The drama of this moment is heightened all the more as it is clearly set against the backdrop of the French city and the Casbah – two worlds forever locked in mutual antagonism.

On my latest trip to Algiers, I climbed for the first time the hill to Notre Dame d'Afrique. This church is visible practically everywhere in Algiers, but on all my journeys to the city I had never got round to visiting it. During the 90s, there was a permanent police presence here and the priests were under 24-hour protection. When I got there, I found the atmosphere relatively relaxed. It was a sunny day and the esplanade around the church was thronged with families, picnicking, enjoying the views (which are some of the best in Algiers), kids playing football. The terrace overlooks the district of Bologhine, which contains the football stadium and the Christian and Jewish cemetery. The seafront houses look like a small town from Brittany or Normandy that has been grafted on to a Mediterranean vista.

Inside the church, a handful of elderly pieds-noirs were at prayer. I chatted to a few, who told me that this was still their home and that they prayed for peace, which they hoped for but never expected to see. Over the altar is the rubric "Pray for us and the Muslims".

Outside in the sunshine, I chatted to the families and children at play. I asked them if they had ever been inside the church. I asked one kid, about 10 years old, wearing a Chelsea shirt and kicking a ball, if he knew what the building was. "Eh bien oui," he said in perfectly accented Mediterranean French that could have come from Marseille, "ça c'est la mosquée des Roumis. Mais il n'y a plus de Roumis." Oh yeah – that's the mosque of the Romans. But there ain't no more Romans.

In Algiers in the 21st century, the French may have left but France is still the enemy. It also represents the promised land. By day, the streets of downtown Algiers are thronged with unemployed young men who dream of France but have no chance of getting the visas they need to get there. The visits by President Chirac in 2003, then Sarkozy in 2007, and, most recently, François Hollande at the end of last year have all been met by crowds chanting: "Give us our visas!"

The Algerians who have made it in France can find the atmosphere strange and unfriendly when they come back. Sinik, a rapper in Seine-Saint-Denis, came over and swore that he would never come again: he was met by heckling crowds and general indifference. For a whole generation, so-called democracy has made Algeria feel like a prison. They don't need to be taunted by those who have escaped.

No one really knows exactly when the last "war for liberation" ended. All everyone knows is that the rate of killing has slowed down but nobody feels free. The tension hangs in the air, waiting to be transformed again into an electric storm.

The French Intifada, by Andrew Hussey, will be published by Granta in the autumn

Labels: Algeria, Colonialism, Conflict, France, Islamism

<< Home