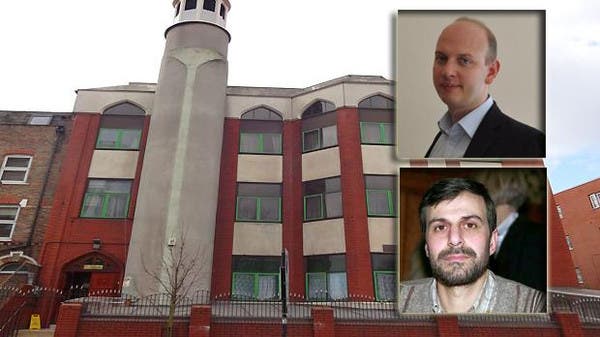

London's Finsbury Park Mosque detains journalist

The manager of the London mosque (Bottom Right) does not react well

to one journalist’s (Top Right) questions about apparent ties to the

Muslim Brotherhood. (Courtesy: Facebook)

Abu Hamza al-Masri’s sermons attracted the likes of 9/11 conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui and failed shoe bomber Richard Reid, earning the mosque the reputation as a “suicide factory” and “Al-Qaeda camp in the heart of London.”

The dark days of Abu Hamza are long gone: Finsbury Park Mosque came under new management in 2005; its hook-handed former imam was this year convicted of 11 terrorism charges in the United States.

But as the mosque continues to rebuild its reputation, I can offer a few words of PR advice: Generally speaking, it’s best not to lock journalists in rooms against their will, no matter how much their questions may irk you.

Earlier this year, I was commissioned to write about the so-called “new era” at Finsbury Park Mosque.

I duly contacted Mohammed Kozbar, manager of the mosque, to arrange an interview and met him there in early July.

I began by asking about the transformation of place – its new relationship with the wider community, how the congregation has changed, and how it still suffers from the Abu Hamza link despite the change in management.

Kozbar answered these questions, but was less chatty when it came to my next line of enquiry.

I asked if the mosque had any links to the Muslim Brotherhood, an organization that has come under the scrutiny of the British government and is banned in Egypt, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

Kozbar quickly became defensive, saying that this was not the agreed subject of the interview. I argued that any political affiliations of the mosque management and trustees seemed to me very much on-topic; Kozbar reluctantly answered some questions on the matter.

Locked in

But things took a turn for the worse immediately after the interview. Kozbar demanded a copy of the interview tape, something I said I was happy to provide on the spot. But as I was in the process of complying with that request, Kozbar called the police, saying that he was suspicious of my journalistic credentials. The door of his office was then locked, effectively imprisoning me in the mosque.I then spent the next 30 minutes asking to be let out of the room, with Kozbar and another man who did not identify himself refusing to let me go. I too dialed “999” to alert police that I was being held there against my will.

Kozbar and his colleague insisted that I produce certain identification documents before they let me out of their office; otherwise, I was to wait until police arrived.

As a freelance journalist having recently returned from an eight-year stint in the Middle East, I have not yet renewed my membership of the National Union of Journalists, and so was unable to produce the NUJ card that Kozbar requested.

I did however show him an email from the commissioning editor specifically commissioning the story, along with several other forms of identification and my media credentials from previous work.

None of that satisfied Kozbar, who kept me locked in his office for about 30 minutes until local police arrived, despite my emphatic pleas to be released. After brief questioning and identity checks by police, I was free to go. I decided not to press any formal charges.

‘Islamophobic’ attacks

I telephoned Kozbar the next day, when things were calmer, to ask about his motivations for locking me in his office. He said he was worried I was a “malicious” journalist who was somehow misrepresenting myself.I called him again on Aug. 19 to speak about the incident, noting that I would be writing about it in an article. During the brief call, he denied he had locked me inside the mosque and said he would not comment any further, adding that the case had been closed.

“From my side, the issue is closed," he said. "At the moment I have nothing to say,” he said.

I do have some sympathy with Kozbar. Given the history of the mosque and the seemingly indelible link with Abu Hamza, it has had an understandably rough ride in the press.

More serious hangovers from the Abu Hamza days persist, with the mosque having faced numerous attacks in recent years. There was an attempted fire-bombing; an envelope containing white powder was mailed there; someone even put a severed pig’s head on the front gates.

During the recent trial of Abu Hamza, the mosque continued to receive “nasty” emails and letters, Kozbar said. That’s despite the undeniable transformation of the place from extremist den to community centre. Nowadays, the once-notorious mosque is more likely to be visited by interfaith groups, local residents or council workers than trainee terrorists.

Muslim Brotherhood

Yet this new spirit of openness does not appear to extend to the mosque’s apparent links to the Muslim Brotherhood.In 2005, after Abu Hamza had been arrested by UK authorities on terrorism charges, a group under the umbrella of the Muslim Association of Britain (MAB) was asked to take control of Finsbury Park Mosque.

MAB was founded in 1997 by the Egypt-born Kamal El-Helbawy, who was at the time a prominent spokesman for the Muslim Brotherhood. The organization is currently headed by Omer el-Hamdoon, who freely acknowledges that the MAB is influenced by Muslim Brotherhood thinking, although tells me that it is not a formal part of the organization. El-Hamdoon also says MAB has “a say in how things are run” at Finsbury Park Mosque.

Mohammed Kozbar is vice president of MAB, as well as its head of PR and politics. But he claims that this does not imply any link with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Government enquiry

A few weeks after the rather eventful interview with Mr Kozbar, Finsbury Park Mosque found itself the subject of media attention once more.At the end of July, it emerged that the mosque and some other Muslim organizations had had their bank accounts closed by HSBC, causing outrage among some community members.

HSBC did not give an explicit reason for the closures, saying only that the organizations fell outside the bank’s “risk appetite”.

Yet another of the organizations to have had its bank account closed was the Cordoba Foundation, which British Prime Minister David Cameron once described as “a front for the Muslim Brotherhood”.

Wider questions about Muslim Brotherhood-linked activities in the UK have been raised in the wake of a government inquiry as to whether the group has links to extremism or violence.

The government report, which was expected to be published in July, has not yet been publicly released. According to the Financial Times, ministers and officials are still “wrangling” over its apparent claim that the Brotherhood should not be labeled as a “terrorist organization.” Such a finding would upset the UK’s Gulf allies, the newspaper said.

Whatever the outcome of the report, it is clear that there is heightened interest in activities of the Muslim Brotherhood in the UK, which reportedly operates from an unassuming office above a disused kebab shop in North London, where I have also visited to conduct interviews and was treated fairly.

And so it was surprising that Mr. Kozbar of the Finsbury Park Mosque should react so strongly when I asked him whether the Brotherhood has any influence over his organization.

That is especially the case as the mosque continues to rebuild its relationship with the wider community, as it has clearly been doing. The local MP Jeremy Corbyn has held meetings at the mosque; it is also used for community outreach programs and forums to tackle issues like disability and the environment.

“We open our doors to everybody,” Kozbar told me early on in our interview.

Yet some doors, as I found out later, remain very much shut.

Last Update: Monday, 25 August 2014 KSA 18:34 - GMT 15:34

Labels: Britain, Immigration, Islamists, Muslim Brotherhood

<< Home