Advancing Science Through Warfare

"They were using cutting-edge technology one hundred years ago developing chemical weapons."

"That was high technology at that time, and here we are one hundred years later using high technology again to remediate the material left behind."

Alex Zahl, project manager, United States Army Corps of Engineers

"They're still fascinating reminders of a remarkably little-known but important chapter in American history."

"A secret archaeological site in the forest."

Elliot Gerson, 66, Period home-owner, Dalecarlia Reservoir

|

Searching for WWI Munitions Buried in D.C.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers scours the Spring Valley area in search of WWI munitions and fragments.

|

The Dalecarlia Reservoir represented one of the main water sources for the city of Washington, D.C. There, under a canopy of trees, a team of geophysicists survey the forest floor for relics from the First World War with an electromagnetic scanner looking to harvest data relating to objects lying deep in the soil. It is a place where one hundred years ago mortars and artillery shells hit, launched from American University where scientists developed chemical weapons, explosives and gas masks for use during the conflict.

Remnants of experiments are also being unearthed. World War I, also called the Great War, one that inspired those who experienced its horrors to name it the war to end all wars, infamous for its horrible battlefield conditions, was responsible for the death of 8.5 million soldiers, the agonized wounding of another 21 million -- though assuredly it was not among the military alone that the Grim Reaper found enough corpses to keep his great mortuary busy for years to come.

On the scientific side of things a kind of inventive progress was made with optics, radio and sonar while German submarines prowled the seas and aviation came to maturity at the conflict's conclusion. The U.S. Navy hosted the scientific knowledge of Thomas A. Edison. The National Academy of Sciences anticipated a need for collaboration among scientists, universities, industry and the military even before America entered the war after it had raged for two years.

The National Research Council was established in 1916 by then-President Woodrow Wilson. Once he signed the war declaration in 1917, the National Academy's foreign secretary sent a telegram to counterparts in Britain, France, Italy and Russia reading: "The entrance of the United States into the war unites our men of science with yours in a common cause". And in that common cause top physicists, chemists and engineers volunteered to work in scientific solidarity.

|

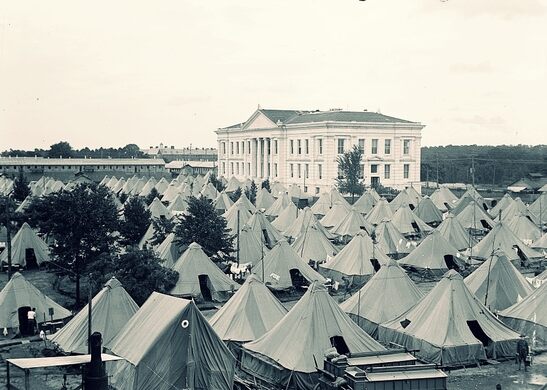

| American University surrounded by army tents Library of Congress [public domain] |

Germany had launched a surprise chlorine gas attack in Flanders, Belgium at a time that the U.S. Army had no protective gear, and no capability to produce, much less deploy chemical weapons, and nor did doctors have any experience with gassed or chemically afflicted soldiers. Which led the War Department to set up a laboratory they named the American University Experiment Station and by the end of the war close to two thousand soldiers, scientists and civilians worked at the campus and at its outposts throughout the country.

By the time the war ended in 1918, scientists at the campus revealed their development of a new weapon they called lewisite, a blister agent based on arsenic reportedly to be dropped on the Germans in 1919 should the war not have ended by then. Post-war, the experiment station reverted to American University and over the succeeding decades developers turned the surrounding land into an affluent residential neighbourhood.

In 1993 developers dug up a cache of mortars, leading to a commitment to finally clean up the area. Mr. Gerson and his wife Jessica Herzstein bought a home where her parents had once lived on the property, where the Corps investigated and cleaned up the area to ensure no health concerns remained. On the wooded slope above their driveway, weeds cover a concrete platform that was once a launch pad for the experimental mortar range.

Two ivy-draped bunkers are to be found behind the house, which Mr. Gerson calls evidence of century old scientific endeavours, pointing to holes in the walls where scientists likely pumped gas into the chamber, a memento of the dread weapons once tested there.

Labels: Chemical Weapons, Science, Technology, United States, World War I

<< Home