The Beauty of Islam

"I had nothing to do with any of this [Syrian Sunni protests against the Alawite regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad] before I was working and then going home. I hadn't even taken part in the demonstrations."

"They [Syrian prison guards] ask you in prison who is your lord. If you say God, they torture you more. You must say it is Assad."

"As soon as I was well enough [after his discharge from prison in Syria] I joined the fighters [rebel Sunni Syrians battling the Syrian regime]."

"It's true that I have been through all this but I'm not upset. It's all for the sake of God. This is what God has written for me. Our prophet would fight for the sake of God and be rewarded. I will be rewarded for this in paradise."

Abid Borhun, Syrian refugee, Reyhanli, Turkey

This man, Abid Borhun, lives with his wife and their four children in Turkey now. He once fought with the Syrian Sunni rebel group calling itself Ahrar al-Sham. But before he had decided to join the rebels he had no connections whatever to the growing protest movement. This was a man, an ordinary citizen of Syria, who remained beyond politics, as he saw it being played out, between Shiites and Sunnis in his native Syria.

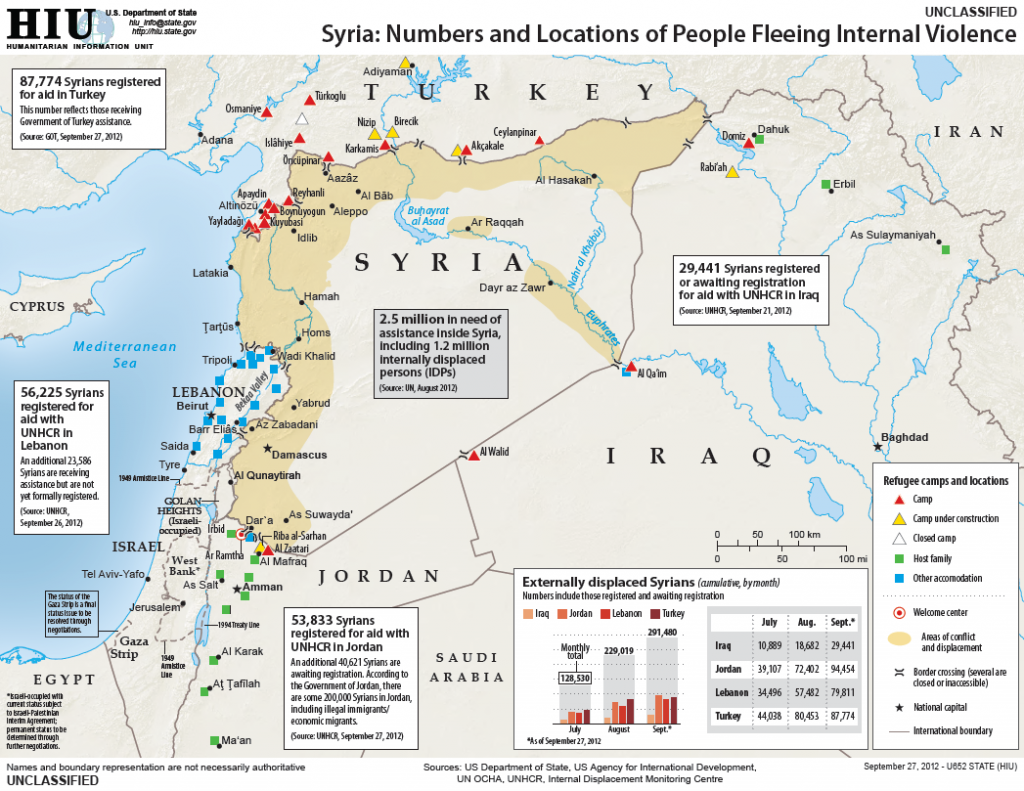

Now he lives in a border town where Syria and Turkey meet, along with thousands of other Syrian refugees. His children are young, ranging in age from eight to 18 months. He has named his youngest boy Ibraham, but calls him Erdogan in honour of Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan to whom he feels grateful that he and his family have found haven.

As a businessman, busy shaping his life in the capital Damascus, Abid Borhun, might never in his wildest, most bleak nightmares have imagined a time when he would not be hale and capable, the master of his own fate. But he is a paraplegic, unable to move his legs, his arms, requiring that he be propped up. He suffered a severed spinal cord, three shattered vertebrae. Bullet fragments remain in his chest. A colostomy bag collects his waste.

"I tried to scream but no sound came out", he tells an enquirer, asking what had happened to him. Crouched with his rebel group in a shallow trench, preparing to launch a nighttime attack on a hilltop where Syrian army soldiers were stationed in northern Syria, he was hit by a sniper's bullet, through his neck. He felt certain he would die. The shahada slipped in a whisper from his mouth, leading him with a reverence for his spiritual investment in Islam, to death, and peace.

Instead, he survived, ending up at the Turkish border. Permitted entry, months of medical treatment followed in Turkish hospitals. This man who never entertained thought of protesting against the repressive government that ordained his life, was arrested on his way home on the outskirts of Homs. He was accused of terrorism. "What I saw in prison I hadn't even seen in films. I felt near the end of my breath", he told his interlocutor.

Beaten, hung by his wrists tied behind his back, he was electric-shocked. He was treated to a process whereby he came close to drowning. Then he was fitted and forced into a tire. And for twelve hours he was left squeezed into the tire before being released. He was released because he had been forewarned that if he 'confessed', in hopes of releasing himself from torture, he would be killed. Two months later he was released, ill and disillusioned.

And that's the point at which he joined the rebel militia, after he had recuperated from his ordeal. He is not bitter. What he experienced, he emphasizes, is what God had ordained for him. And if it is God's wish that he remain as he is, a shadow of what he was, he is content. Islam, the faith that instructs its faithful to slaughter the infidel, and to dedicate their lives to jihad, inspires him.

He does think about his country, and he hopes that the Sunni Syrian rebels will manage somehow to defeat their bloodthirsty president who destroys the lives of his citizens through chemical weapons, barrel bombs, starvation and privation geared toward killing more than the half-million he has already slaughtered. In this sectarian war. Where one branch of Islam has a venomous detestation for the other. Where either branch of Islam feels that the other represents apostasy.

"I want everyone to know about the beauty of Islam", he says. "I want Islam to spread. No matter what country, I want Islam to spread."

Heaven forfend!

|

| Turkey’s Yayladağ camp for displaced Syrians. CRISIS GROUP/Hugh Pope |

<< Home