Rio: From Bad To Desperate

"The situation is one of complete vulnerability."

"The weapons used by the traffickers are weapons of war."

Antonino Carlos Costa, head, Rio de Paz

"To the extent that you were reclaiming territories of the favelas from drug traffickers, you needed to create jobs."

"There was an expectation that there was going to be a massive investment in social projects in the favelas, and then the money ran out completely."

Monica de Bolle, expert on Brazil, Peterson Institute for International Economics: Corruption

"They come to us with a discourse that there is a war."

"But this is not a war. It's a massacre of poor people living in favelas. To ensure that the elite enjoys security, it's necessary to kill the poor people."

Ana Paula Oliveira, community activist

|

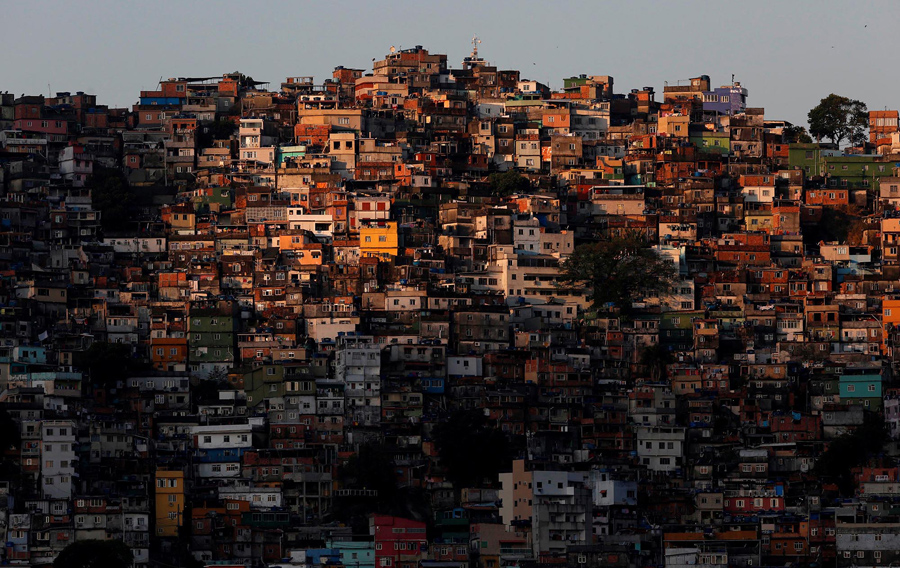

Brazilian army military police patrol an alley in

the Rocinha favela in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on September 25, 2017.

Shootouts had erupted in several areas of Rio on September 22, prompting

Brazilian authorities to shut roads, close schools, and ask for the

Army to intervene. Mauro Pimentel / AFP / Getty

|

Gangs have been proliferating in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The police response has been harsh, and they have themselves buried 119 of their own this year alone, while increasing territory has been surrendered to drug gangs with their open-air sales in the favelas. These are the communities, teeming with the poor and the disadvantaged and the forgotten that had been proclaimed as having been "pacified" several years back.

This city of 6.5 million appears to have accepted that endemic violence, crime and murder finds it place in their city. They have apps on their cellphones to alert them where gunfire is live to enable them to decide whether to take their usual commute to work or search out an alternative. No fewer than 4,974 people were killed in the nine months of this year in Rio de Janeiro State, elevated by 11 percent from last year's statistics.

Rio de Janeiro is bedevilled by increasingly well-armed, organized drug cartels, and a budget deficit. They now look for backup in their plight to the military, and hope the federal government will help rescue them with a bailout. While preparing to play host to the 2014 World Cup and bidding for the 2015 Olympics, authorities set out to secure the city's favelas, long neglected by government. Community policing was introduced with law enforcement officers suitably rewarded for meeting crime reduction targets.

|

| Soldiers patrol Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro on September 25, 2017 Carl De Souza, Getty, AFP |

The counterinsurgency strategy seemed to work. Calling them Pacification Police Units the plan was to bring state services to the long-neglected poverty-stricken, underserviced areas. The presence of police was meant to discourage organized crime networks which had been operating as the de facto authority in the favelas during the long period of neglect; from there gradually expanding access to sanitation, health care and education introduced to the marginalized communities.

The result was initially that the peak of 65 violent deaths per 100,000 Rio de Janeiro State residents in 1994, saw the rate dropped in 2012 to 29, a resounding success by any measure. An infrastructure investment of $10.7-billion, before the 2015 Games, seemed to herald a future where the Olympics was to become a catalyst for the reduction of inequalities in a city where exorbitant wealth and excruciating poverty had co-existed for far too long.

According to federal prosecutors, state officials did what comes naturally in many such situations; the spending on the Olympics became an opportunity for fraud where hundreds of millions was siphoned off by the former state governor and his minions. Public transportation had been upgraded thanks to the Olympics but little else of lasting value resulted from that world sport event. Because of the ongoing violence, schools in the area are forced to shut down days at a time, fearing stray bullets.

Young men carrying rifles man entry points of a sector in favelas controlled by drug traffickers, while schoolchildren walk their way to school through the narrow streets and stands of produce stand beside tables where bags of cocaine and marijuana are hawked by sidewalk vendors. In Copacabana and Ipanema tourists have not been spared the violence, resulting in a loss of about $200-million in tourism revenue for the city between January and August.

The secretary of security for Rio de Janeiro State explained "we need financial resources that the state does not have at its disposal", to be enabled to provide for increased, more reliable security. No one, it seems, speaks of providing opportunities and job prospects for favela dwellers to keep the young from lending themselves to the drug cartels and the gangs.

|

| A view of the Rocinha favela on September 26, 2017 Bruno Kelly, Reuters |

Labels: Brazil, Corruption, Crime, Drugs, Poverty

<< Home