An Ambitiously Atrocious Experiment

An Ambitiously Atrocious Experiment

"When you see something that is technically sweet, you go ahead and do it." “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

"We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent." J.Robert Oppenheimer, head, Los Alamos Laboratory, the Manhattan Project

|

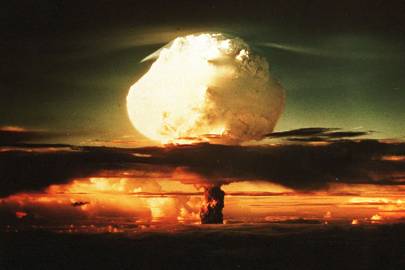

A photograph on display at The Bradbury Science Museum shows the first thermonuclear test on October 31, 1952 Bradbury Science Museum / Getty Images |

"There's just no comparison [between the first atomic bombs and present-day nuclear weapons]; the shift in our nuclear arsenal is astounding." "When you have the leaders of countries issuing nuclear threats on [Twitter], that's a serious development." "The world is sleepwalking its way through a newly unstable nuclear landscape." "Any belief that the threat of nuclear war has been vanquished is a mirage." "[The trend for] tactical [weapons doesn't make us safer." Sharon Squassoni, global security expert, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

"The overall trend has been away from mass destruction to prevision, reducing collateral damage." "However, the argument goes that precision actually makes it more likely that we might use them." Seth Baum, executive director, Global Catastrophic Risk Institute

"The idea was to explode the damned thing," "We weren't terribly concerned with the radiation." Hymer Friedell, Manhattan Project

"[In Hiroshima many survivors were brought to the Hiroshima Communications Hospital, to the care of Dr.Michihiko Hachiya." "They began vomiting, leading the doctor to wonder whether] the new weapon [threw] off a poison gas or perhaps some deadly germ?" "Unconsciously, I grabbed some of my hair and pulled ... The amount that came out made me feel sick." Dr.Michihiko Hachiya, Hiroshima Communications Hospital

Dr.Hachiya had just completed his air raid duty, noting in his logbook that there was nothing to report. The residents of Hiroshima were accustomed to hearing the American bombers overhead, but for some reason unknown to them the bombs never rained down on Hiroshima, as they did elsewhere in Japan. Hearing the planes pass overhead, the residents felt no tense expectation, just a casual acceptance that this was what U.S. B-29 bombers did.

Dr.Hachiya noted that "The hour was early; the morning still, warm and beautiful." Overhead flew a plane called the Enola Gay, and it carried a new device named Little Boy. Mere hours earlier in the New Mexico desert the first ever produced atom bomb had been detonated. "The whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun", observed General Thomas Farrell, deputy commander of the Manhattan Project, Los Alamos.

The "Trinity" test completed, Little Boy headed toward the Southwest Pacific in a ship. The crew of the Enola Gay discover their mission and are informed that the bomb they are set to release over a Japanese city is powerful enough to crack the Earth's crust. That night a clear night sparkling with shooting stars lay over Hiroshima. The crew of the Enola Gay is given four cyanide capsules, one for each member of the crew, should they be captured.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/mco/EJWUHIRT2BHSPPLUPYFJFK4FQE.jpg) |

| WWII veterans recall the tough missions leading up to Hiroshima and the efforts to hide the Enola Gay, seen here returning from dropping the atomic bomb on that city 75 years ago today. (AP Photo/Max Desfor) |

Early morning, their flight close to their destination, the 4,400 kg warhead is armed. Two hours later, a tone alerts the crew to prepare for the explosion. At 8:15 a.m. the bomb bay doors release Big Boy on a beautiful sunny morning, and a fireball hotter than the sun appears, vaporizing everything within a mile, instantly killing a quarter of the 350,000 residents of Hiroshima. Those who survive the initial blast are naked, their clothing seared into their backs, wandering about within the inferno.

The sky that was so clear and the sun that shone its warmth and light down onto the city have been eclipsed, and black rain envelopes the city. Survivors have no memory of the great boom the explosion caused; recalling only the flare. And the silence. "That beautiful cloud! I have never seen anything so magnificent in my life!", enthused one mystified survivor. The Enola Gay returned to its base.

|

| Peace Memorial Park cenotaph atomic bombing in Hiroshima, (Eugene Hoshiko/AP) |

Since the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, weapons whose power have been exponentially magnified have emerged. Spurring bans and treaties. In 1986 there were 70,000 nuclear weapons globally; that number now stands at 14,000. How many such weapons of dreadful killing magnitude would it take to turn the globe into a burnt ember?

Technology never looks back, only forward. Hypersonic delivery systems have been designed to evade missile shields to high-altitude strikes, disabling communication networks. The creation of the atomic bomb took much furiously intensive creative thinking and careful experimentation. Refining the bomb, making it infinitely more destructive was a relatively relaxed task in comparison to the deep experimentation required to build the first nuclear device.

| |||

| A minute of silence for the victims of the atomic bombing. (Eugene Hoshiko/AP) |

Now, miniaturized and still powerful nuclear devices are on the cusp of the future, where terrorist groups dream of arming themselves with the world's most destructive weaponry. Back in time, 70 years ago, the navy secretary informed Harry Truman that Japanese survivors held open to them "a unique opportunity for the study of the medical biological effects of radiation". Scientists arrived in Japan to study the survivors.

Five years later, 130,000 survivors had been 'enrolled' in the Life Span Study, its results forming the world's larget bank of data on the effects of radiation, helping to develop safe medical uses, like CAT scans and X-rays. The Survey remains active; now studying the effects of the nuclear detonation on the next generation of children. "Some people didn't want to go naer them because they were 'infected'", Takuo Takigawa, director of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum notes.

Hibakusha, as survivors and their offspring were called, were not permitted use of public baths fearing contamination. They were unable to find employment, rejected as survivors contaminated by radiation, viewed as societal castoffs. There was a reason that U.S. bombers refrained from bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The purpose was to be able to study the total annihilation and material effects of the atom bomb from a clean slate.

Valuable scientific and medical information was derived from studying the effect on human habitation and human life, destroyed by a nuclear blast. Resembling nothing so much as Nazi medical experimentation on slave labourers and concentration camp inmates. The most infamous of these experiments were carried out under the precise instructions and directions of SS physician Dr.Josef Mengele, at Auschwitz.

|

Two women and a child, subjected to medical experiments —-- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |

Out of his experiments where living human beings == many of them children, and infamously twins, were routinely tortured, experimented on, most frequently perishing from the rigours they suffered -- came data on the conditions under which human life would be forfeit. Sterilization, artificial insemination, extreme temperatures, poison and wound experiments and many others on an ad hoc basis were carried out on helpless prisoners. Their results formed the basis of an entire range of data compiled into medical texts.

These 'research' results made their way into reputable medical journals as data that could never have been assembled under universal medical/scientific rules of research. Yet these data have been used as valuable insights compiled on living human beings by meticulous note-taking on the part of cold-blooded medical professionals whose oath of conduct would have included the ancient, revered code of 'do no harm'.

Labels: Japan, Medical Nightmare, Nazi Germany, Nuclear Technology, United States, World War II

<< Home