Hollowing Out Guatemala

"We have to create better opportunities for people so they can stay home."

"We also have to work on countering smugglers who have convinced people that their best opportunities to be successful lie in the [United] States."

Victor Manuel Asturias Cordon, head, National Competitiveness Program, Guatemala

"No one will turn them in [report smugglers to the government, even for rewards], because within the community they are not seen as bad people."

"But everyone knows who they are."

Dora Alonzo, Quetzaltenango anti-migration group

As for the United States, while it is doing its best to discourage migrants from illegally entering the United States for underground work, it is also planning to invest over $200-million on projects over the next few years in the western highlands of the country to ideally create jobs and reduce endemic poverty. Few people interviewed in Quetzaltenango, the largest city in the Guatemalan highlands claim to have seen or heard the warnings.

Even had they seen them, many of those interviewed stated baldly those efforts would be wasted in persuading them to remain in Guatemala, convinced that opportunity, good employment and prosperity awaits them on entry to the United States. Residents of the city do see advertisements by the smugglers, on the other hand, and at least one community radio station in the city helps promote the smugglers' offer to transport and aid in financing northbound travel.

In the past year alone, 42,737 Guatemalans chose to travel as family units only to be apprehended or stopped at the border between the U.S. and Mexico, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection. That number represents close to fifty percent of all migrants seeking entry to the United States with their relatives for that period. In Concepcion Chiquirichapa, a town where about ten thousand people live, everyone has family or contacts in the United States.

And the residents explain that the extreme poverty they live with is their sole motivation where about 75 percent of the population lives an impoverished life and where 67 percent of children under five suffer chronic malnutrition, the U.S. Agency for International Development figures attest. In the country, over a million people in rural areas have no access to electricity and many earn scant profit from coffee, corn, beans and other produce they grow.

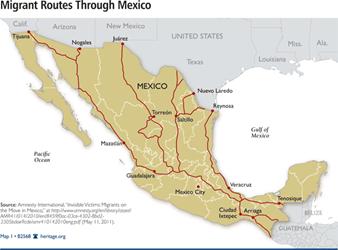

And nor are their lives immune from the deleterious effects of drug trafficking, widespread corruption through local government and gang extortion, all of which aggravations, dangers and fears associated with them, conspire to influence their decisions to leave. Once that decision is made, people face a 1,900-kilometer journey to reach the U.S. For some, failures leading to return, only makes them determined to make the same attempt time and again until they succeed.

|

Despite the experience of facing countless dangers such as unscrupulous smugglers, fraught desert crossings and the possibility of being kidnapped by members of the deadly Mexican drug cartels. What propels them are the feelings of hopelessness in remaining in Guatemala where opportunities for a decent living wage are scarce and safety and security never a guarantee.

The billboards, radio and television warnings by the U.S. and Guatemalan governments alerting people against the dangerous journey to reach the United States go unheeded, if they are seen at all. Thousands determined to seek work and the prospect of a better life continue to flee the western highlands of Guatemala, their remote, rural, impoverished homes.

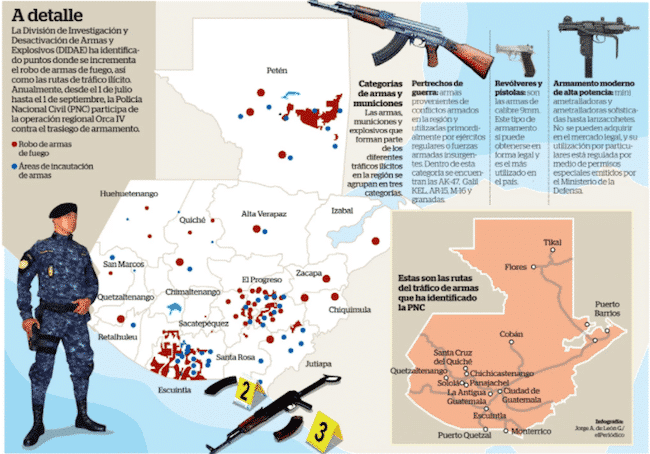

And to complicate things even further, there are smuggling routes into Guatemala where guns and drugs are being run. In the opposite direction, into Guatemala. Not into the rural areas where people are fleeing from, but into the centre of the country, its largest cities where criminal gangs tend to operate. A scourge that has contaminated the quality of life in most Central American countries.

<< Home