The World Wide Search for a COVID Vaccine

"It's always a question of dollars for research -- there's never enough to do everything you want."

"So unfortunate situations like this do forces people's and politicians' attention on the need to do that ... I think there will be big consequences."

"It's [the novel coronavirus] really a chemical. It's inert. They're not alive or dead, they're inactive or active."

"They're parasites, by definition that's what they do -- they take advantage of a host."

Roy Duncan, virology professor, Dalhousie University

"HIV research really took off in the late '80s and early 90s, taught us how the virus replicates."

"We're kind of with anti-virals now where antibiotics were to the 1950s ... This particular [COVId-19] virus is going to really dramatically accelerate a lot of work."

Dr.Gerald Evans, chair, infectious diseases division, medical school,Queen's University

"In the face of this pandemic, where public health measures are not sufficient, it is going to propel research further."

"[It] is enhancing and will likely increase the number of anti-virals being developed and tested."

Joanne Lemieux, biochemistry professor, University of Alberta

|

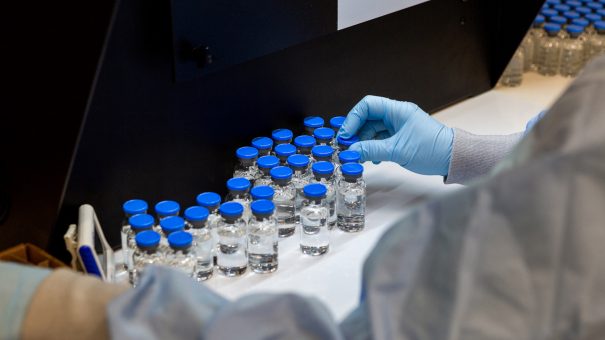

| Cobra Biologics, working on a potential COVID-19 vaccine. |

In part as a result of the unique, parasitical qualities of viruses, research initiatives hoping to treat infections from the flu, the common cold and Ebola have been unsuccessful since they are much more difficult to deal with successfully than, as an example, antibiotics in countering bacterial infections. There have been scant few success stories, overwhelmed by abject failures in coming up with drugs with the properties to treat viral infections.

|

| Gilead’s antiviral drug remdesivir |

To the present, Remdesivir, designed originally for Ebola, and which failed to counter its effects, held out hope for efficacy in the treatment of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. It has just been given regulatory approval in the United States after undergoing a study that affirmed it had a fairly mild effect on the subjects enrolled in the trial, shortening their hospital stays by several days, but doing nothing whatever for the symptoms, much less protecting against the coronavirus.

It is illustrative of the anxiety involved in trying to find a coping mechanism for the SARS-CoV-2 virus that the drug, however modest its effect, will now be the first arrow in the quiver of the novel coronavirus arsenal. Hope remains high that other drug trials will be more successful, not only in alleviating symptoms but eventually even preventing the virus from infecting people as readily as it does, replicating and spreading. Now the great hope is for the discovery of a reliable, safe vaccine to end the pandemic by preventing its contagion.

At one time the HIV infections that causes AIDS killed just about anyone who contracted it 30 years ago. Now patients are able to live long, healthy lives given the drug regime prescribed for that very specific purpose; not able to cure but to suppress the virus to the point that its deadly symptoms are prevented. Hepatitis C drugs represent a new generation of drugs, excruciatingly expensive but representing a breakthrough by curing the disease.

|

| Ampules of Remdesivir |

In "acute" viral infections such as flu, measles or West Nile, a short, sharp onset of symptoms ensue followed by fairly swift recovery -- and sometimes death. And no anti-virals have yet been discovered and certainly not for lack of trying. On the other hand, since they've become part of a controlled background of awareness without quite the same level of dire and immediate threat the COVID-19 infection has become, we live with them and adapt accordingly.

"We really don't have good anti-virals for an acute viral infections", Dr.Srinivas Murthy, head of a Canadian trial of possible COVID-19 drug treatments admitted. And as Dr.Evans adds, it is "a heck of a lot harder" to create an antiviral than an antibiotic. Bacteria represent free-living cellular organisms with the biology to survive and reproduce independent of a host they may invade. They can be viewed as relatively easy targets for drugs.

Viruses on the other hand consist of nucleic acid, genetic material encased in protein. Once they infiltrate a host and stick to a cell, viruses become active and burrow deep into the cell, using its molecular chemistry to replicate, in the process creating additional viruses that will go on to infect other cells. They represent a more difficult, limited target. Added to which difficulty is the fact that drugs must be designed not to be toxic to the host cell, along with the virus attached to it.

|

| Cobra Biologics, Britain, April 30, 2020. |

And then there is the capacity for viruses to mutate, complicating the issue exponentially; they are more difficult to target than bacteria given their mutation tendency, its swiftness and frequency in mutation ensures medication becomes less potent: "Viruses are tricky, they change", noted Dr. Murthy. People's own immune system responding to the presence of an invading virus, can wreak the most damage through dangerous inflammation or sepsis.

Labels: Global Pandemic, Novel Coronavirus, Pharmaceuticals, Research, Trials

<< Home