Arctic Defence and Sovereignty

"[The Arctic is] a sphere of special interest [and Russia's goal is not only to restore its influence there] but to make it even stronger."

"We need to take additional measures so as not to fall behind our partners, to maintain Russian influence in the region and, maybe in some areas, to be ahead of our partners."

Russian President Vladimir Putin - Russian security council

"Unless we, the Arctic countries outside Russia, are there in equal strength, we realistically hand much of the Arctic to him."

"Aircraft, a training site and ships that can move in heavy ice ... You keep building on all of that, operate from positions of strength and keep making the investments necessary to do it."

General Rick Hillier, former Canadian chief of defence staff

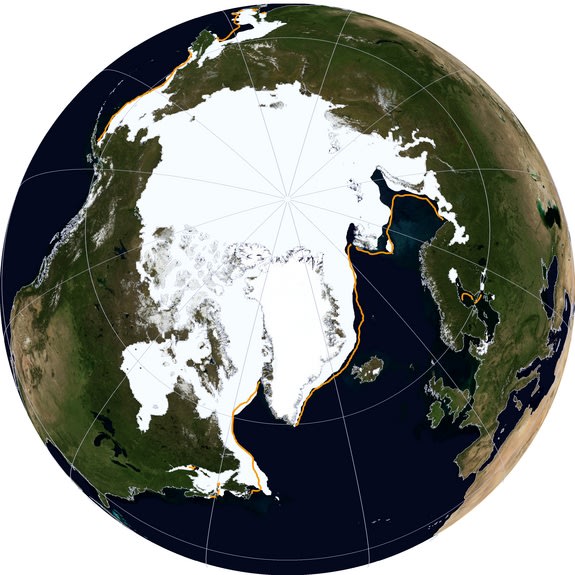

Russia has been busy in the Arctic and it is serious about its influence and presence in the Arctic Circle. It has several million people living north of the Arctic Circle, and it has a history of Arctic exploration to match that of Great Britain's and Norway's. In the process of building up its military infrastructure including the refurbishing of two bases 50 km from the Finnish border, it is busy creating a new Northern Fleet intelligence unit.

To be staffed by 3,000 electronic warfare specialists, and involvement in developing unmanned surveillance airships and building a 3,000-strong naval aviation unit, Russia's determination to stand tall and unopposed in the Arctic is compelling. Enough so to make its neighbours very nervous indeed, given its propensity for aggressive, threatening action in pursuit of dominance of an area in which it has disputes ongoing for sovereignty rights.

The purpose of all that enhanced security is to ensure the protection of oil and gas production facilities from the potential attacks coming from "terrorists and other potential threats". Potential threats can be assumed to be competition from Arctic neighbours clamouring that they have rights, too, and "terrorists" can be seen to be any who dispute Moscow's right to claim rights they insist are incontrovertibly theirs.

Canada has more of a low-tech approach to the situation, with sovereignty patrols from the air and sea, and the first line of defence represented by the Canadian Rangers, some five thousand mostly Inuit residents armed with Second World War-vintage Lee-Enfield bolt-action rifles. They form part of Canada's armed forces reserves, proudly doing their job to keep an eye on any unusual activities or sightings, which they then convey to the Canadian military.

Canada is constrained by economic considerations from its more ambitiously-stated intentions to defend the Arctic. The question is how Russia can manage to pay for all the advanced scientific and military equipment and installations it intends to place in the Arctic to defend and prosecute its claims. Russia's financial situation despite its vast energy reserves has been faltering lately. And there is the matter of its huge expenditure in Sochi to proudly show the world its prestige quotient.

Maintaining a build-up of military reserves on the border of Ukraine will cost it greatly, not only in sanctions values, but in maintenance costs, that will now extend to investment in Crimea. But that of course, is Moscow's problem. Canada's problem is contending with pressure from NATO to sign on to a co-ordinated response to Russia's aggressive militarization in the Far North. And its resistance to doing just that, by failing to agree on the inclusion of Arctic issues within NATO's purview.

The events in Ukraine have not covered Russia in glory, but they have diminished NATO's reputation simply because the situation, untenable as it is, is one where NATO will not physically intrude. Ukraine is not a member of NATO, but its neighbours, fearful of Moscow's further designs, are. Norway wants to see NATO concern itself with Arctic issues as a counterweight to Russia's indomitable threats of dominance.

Why Prime Minister Stephen Harper continues to be resistant to the inclusion of Arctic issues within NATO's agenda is not quite clear. A September summit to take place in Cardiff, Wales will certainly put the issue on the agenda. "The question is, can you trust Russia? Can any country say this shouldn't be on NATO's agenda?", asked one involved diplomat.

"No western or NATO country is going to risk a confrontation that could turn violent, and then escalate frighteningly over Ukraine -- viewed by most as 'far away and corrupt as hell'", stated Mr. Hillier of Russia's strategic priorities in enlarging its hegemonic comfort zone. Vladimir Putin accurately judged the constraints placed upon NATO with respect to confronting him on the Ukraine file.

But NATO members involved in the Arctic would prefer a more proactive role for NATO in the Arctic to deter Mr. Putin from attempting to pull off anything similar to what he has managed to do in Ukraine, utterly destabilizing the country, and threatening to incur even greater damage should it move from caution to full-throttle defence against the insurgency that the Kremlin has engineered to its advantage.

Canada, according to General Hillier, has focused well on the Arctic with a combination of fighter jets, satellite coverage, drones and underwater sensors for advanced warning of any possible intrusion. But three recommendations were advanced through the recently released Strategic Outlook, by the CDA Institute: Canadian participation in a ballistic missile system; creation of a maritime NORAD, and an adequate number of ships to patrol, to enhance Arctic sovereignty.

Placing the Arctic issue on the NATO agenda might be seen properly as yet another priority.

<< Home