Sparse Employment, High Poverty

"Today, First Nations stand in solidarity with Indigenous peoples everywhere to revitalize and restore our collective rights as peoples and to support one another in that goal."

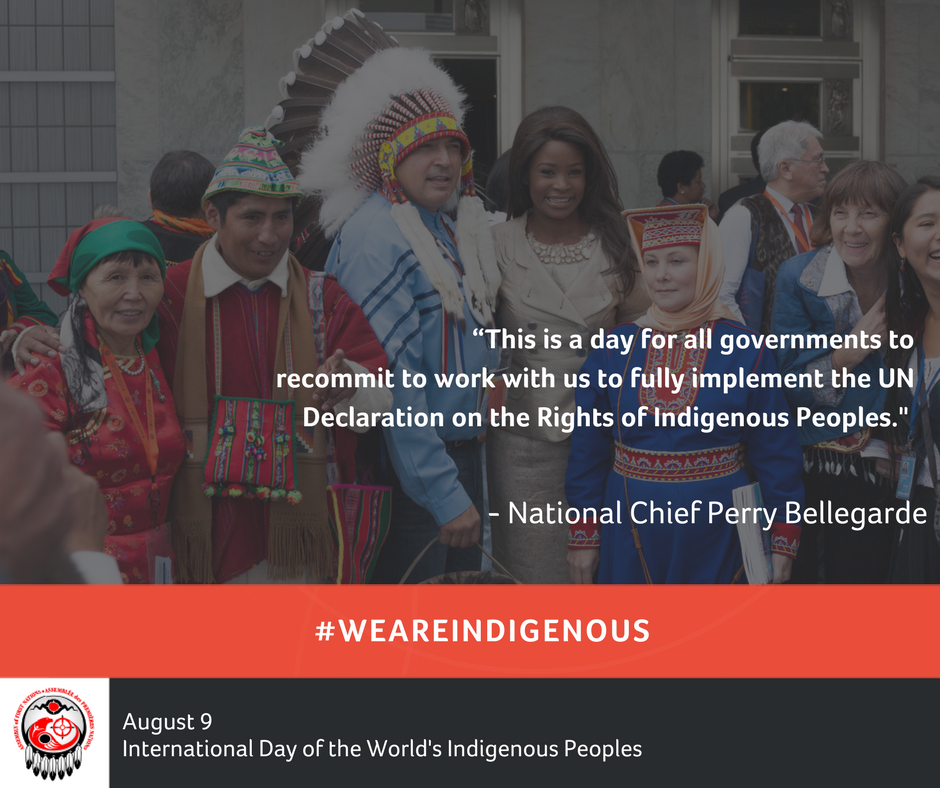

"This is a day for all governments to recommit to work with us to fully implement the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The Declaration affirms Indigenous peoples’ right to self-determination and sets out minimum standards for their survival, dignity and well-being." "Implementing the UN Declaration will promote peace and help close the gap in the quality of life between First Nations and Canadians. Canada has stated its unqualified support for the UN Declaration and, as we approach the 10th anniversary of its adoption by the UN General Assembly, it is time to work together to give life to the Declaration in Canada and around the world."

AFN [Assembly of First Nations] National Chief Perry Bellegarde.

Last week, Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde stated that a meeting is due between Indigenous, federal and provincial leaders to work on closing the economic gap among First Nations, to more closely resemble income levels of the wider Canadian population. This, when billions of dollars are earmarked and dispatched annually in support of First Nations aboriginal reserves. The AFN insists that First Nations tribes continue to live in reflection of their heritage, on often-remote areas of the country difficult to access.

Most people who chose to live away from urban centres on properties where services are absent are on their own; they must themselves provide potable water from wells for themselves, and access to medical care is fairly inconvenient, necessitating long drives to reach hospital and medical centres. Schooling for children can also be a problem, where children are bused to local schools in nearby towns taking hours of commuting time out of peoples' daily schedules. Those committed to living rurally and remote accept these conditions as those they've chosen.

The seasonal inaccessibility to many remotely-located reserves ensures that commodities and food ae expensive, and access to potable water often a problem, as is reaction to unstable or seasonal weather conditions leading to wildfires or to flooding conditions. On reserves, residents do not own their homes and as a result make no effort at upkeep. On reserves there is scant employment available other than what the band council doles out, usually to their own family members. This is not living traditionally, this is living in hazardous conditions where poverty is almost guaranteed.

Conditions are further exacerbated by the social conditions that prevail, with alcoholism and drug dependency common problems. As are poor parenting skills and interests in the welfare of children. Leading to a good degree of social dysfunction, made far worse by epidemics of suicide, particularly among children. Violence perpetrated by males against female members of tribal communities is common and frequent. And each time a reserve is faced with emergencies they seem incapable or unwilling or both to execute measures to meet those emergencies, instead calling upon government to solve those social ills.

Complaints are plentiful about unkempt homes requiring replacement because they've never been cared for, about a lack of psychological counselling and medical facilities close at hand, and the quality of the schools to which aboriginal youth are expected to attend until they reach higher grade levels and must go elsewhere to continue their educations. Health is impacted, both physical and mental, but persuading health and medical professionals to commit to living in hardship posts that remote communities represent is difficult.

Now Statistics Canada has released a report on income data retrieved from the 2016 census revealing that four of every five Aboriginal reserves report median incomes falling below the poverty line. A review of census figures for Indigenous communities reveal 81 percent of reserves had median incomes below the low-income measure, considered to be $22,133 for one person. Of the 367 reserves where data was available, 297 communities fell below the low-income measure, and 70 registered median incomes above the de facto poverty line.

Median total incomes below $10,000 were reported for 27 communities, registering at the lowest end. Oddly, women had marginally better incomes than their male counterparts with about 22 percent of female incomes on-reserve over the low-income measure, as opposed to about 19 percent for males. Indigenous peoples living on reserve reflect a significantly younger population than the general community in Canada reflecting a fertility rate exceeding non-Indigenous counterparts. The bad news is a shorter life expectancy and lower incomes.

A mere 26 of the 503 reserves on the Prairies had higher median household incomes where some reported household incomes of up to $70,336, reflecting employment, investments and government benefits, ranging from $13,168 in Manitoba to $114,381 in James Bay, Quebec.

|

| Statistics Canada released another installment of census data Wednesday, this time with a focus on poverty and income. Still from Video |

Labels: Canada, Child Welfare, Crime, Economy, Education, Employment, First Nations, Health, Indigenous, Poverty

<< Home