Demanding Cheap, Sacrificing Safety

"Improvement don't mean sweatshops no longer exist in Bangladesh. This reporter visited one in Dhaka, three days before the Rana Place anniversary. Fire buckets were filled with trash, emergency water bins were cracked and half empty, no one wore safety masks, most workers -- some in their early teens -- were barefoot, wiring was exposed, bolts of fabric and scraps littered the floors, window panes were broken, and the lone stairwell out of the tenement-like building was obstructed by cartons of finished product destined for Russia."

Dana Thomas: Bangladesh Labor Reforms May be in Peril

"[His girlfriend of three years was pregnant], That's why I joined Rana Plaza, [three days before the complex collapsed]."

"'Help me!' people screamed. 'Save me!' they cried. But nobody was listening."

"The labour law in this country is pro-owner, not pro-worker."

"[When oversight reverts to local governance], all will return to how it was when Rana Plaza happened."

Mahmudul Hassan Hridoy, 32, Dhaka, Bangladesh

|

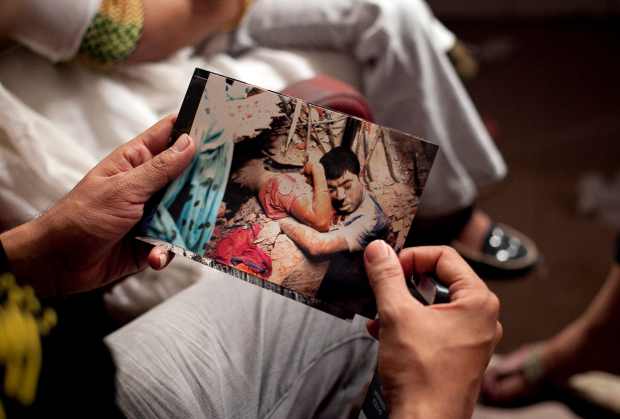

| A Bangladeshi man holds a photo from the Rana Plaza disaster. Photo: Getty Images |

He was a nursery school teacher, but quit the position because it paid so poorly. Then he became a quality inspector for New Wave Style Ltd. for the increased income it promised, at Rana Plaza. He had worked there for two weeks when the collapse occurred. He was working on the seventh floor of the eight-story retail complex when everything crumbled and collapsed and when he gained consciousness it was with the realization that he was pinned under a concrete pillar, and he was no longer on the seventh floor.

He soon enough understood he was now on the second floor, lying beside a good friend, Faisal. Faisal worked on the second floor, as a sewing machine operator. "I'm not sure how, I guess my floor dropped down to his", he explained. And if he hadn't dropped down to the second floor, he might never have known how Faisal died, his skull crushed "And his brains were spilling out. I can't forget how his head exploded in front of me. Those memories still haunt me", he said.

He now walks with a crutch and dreadful headaches assail him His wife couldn't take the change and left. He founded the Savar Rana Plaza Survivors Association which now has 300 members who meet monthly. Two of the members of the group hanged themselves in 2015 and 2016. Opposite the street of the ruined and overgrown Rana Plaza sits a concrete monument of an enormous pair of sculpted fists holding a hammer and sickle, as a memorial to the victims.

India, Vietnam and Bangladesh are recognized as the least expensive places in the world to produce apparel; between them over 4.4 million workers are employed in 3,000 factories where the minimum hourly wage is 32 cents, which comes out to $68 a month. Name brands of respected clothing purveyors make their way to Bangladesh where $30-billion of "ready-made garments" identify Bangladesh as the world's second largest manufacturing center of clothing after China.

After Rana Plaza, those same international fashion brands created two five-year compliancy agreements in an effort to exonerate themselves from an obviously perceived view that they too were responsible for the tragedy, not only the sweatshops from whom they bought their cheaply-produced wares. Over 200 of them signed the legally binding Accord on Fire and Building Safety. The nonbinding Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety was led by Walmart and signed by 28 others, including Gap, Target and Hudson's Bay.

A study released by the Center for Global Workers' Rights last month revealed the impact of the Accord, proclaiming both to be successes citing that in the five-year period, over 97,000 hazards in 1,600 factories were rectified, providing safer environments for 2.5 million workers. "The Accord has undoubtedly saved lives", Liana Foxvog, director of Organizing and Communications for the International Labor Rights Forum, declared.

Unfortunately, both the accord and the alliance are on the cusp of expiring though advocates urge that a new accord be formed. But in Bangladesh there has occurred union repression, and labor leaders have been imprisoned. The Rana Plaza Donors Trust Fund an endowment underwritten by brands to the value of $30 million, compensated Mr. Hrdoy who used the $600 he received to open a drugstore.

Neither he nor the other workers and their families will forget April 24, 2013, when 1,134 workers died, and 2,500 more were injured, in the world's worst fashion garment industry disaster.

|

| A garment worker protest in Dhaka in 2013, demanding a rise in pay as well as compensation for the victims and those injured in the collapse of the Rana Plaza building. Photograph: AM Ahad/AP |

Labels: Bangladesh, Disaster, Garment Factory, Workers' Rights

<< Home